As a PhD-candidate, I remember feeling overwhelmed, baffeled and alone – almost in panic – the day I had finished collecting all data and sat in my office with several hundred pages of transcribed interviews on my desk. What to do know?

Later, I learned that I am not the only one who have struggled with feelings of despair confronted with a large set of qualitative data. Stein Kvale have called it “The 1,000-Page Question” – How shall I find a method to analyze the 1,000 pages of interview transcripts I have collected?

It’s a mystery

Davis Silverman – an expert in qualitative methods – have described qualitative analysis as a mystery. According to what he wrote in the much cited book “Intepreting qualitative data” , it is like “like exploring anew territory without an easy-to-read map”.

The four steps of analysis

Together with colleagues, I have developed a method for grappling with the mystery of qualitative analysis. I have called it “collective qualitative analysis” and the method has four steps: First, go through the data material by presenting abstracts of each interview. Second, mapping data by identifying themes. Third, sorting themes. Fourth, to make a disposition and outline a workplan for the writing process. Together with the other members of my research groups, we have worked through these four steps during 1-2 days workshops.

In this blog post, I will explain how we have worked with collective qualitative analysis, by using examples from my own research projects. Thus, this text is a summary of an article I have published in Norsk sosiologisk tidsskrift called “Kollektiv kvalitativ analyse” (Collective qualitative analysis”.

Preparation

Before the workshop, we had to do some preparations. Most importantly, we wrote summaries of every data item, that is every interview, fieldnote, policy document or whatever data we have been working with. The summaries have been a half to one and a half pages, containing background information about participants, key topics in the interview, the overall narrative presented in the interview (or overall framing in the policy document) and perhaps some reflections about the interview situation.

In the context of work intensive commissioned research, writing the summaries is all the preparation we have done before organising the workshop. For a PhD-project – or research projects with more time and money – I would recommend that you also read through all transcripts, making notes.

Finally, I recommend that each participant prepare a brief overview of existing research and relevant theoretical perspectives for the research project in question.

Step 1: Presenting data

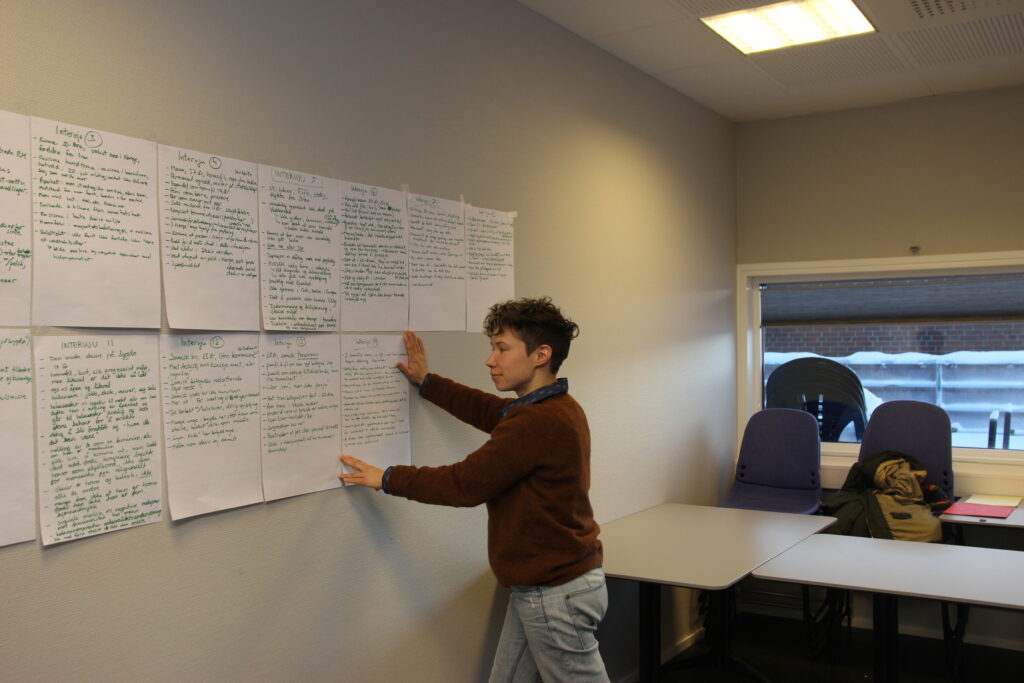

During the first step of the workshop, we presented the summaries of each data item. The one who had conducted the interview presented it, and one of the others took notes. Subsequently, we put the note sheet on the wall so that all data items are visible to the group.

During this phase, we did not open up for discussion or comments. We worked through the entire data material and spent approximately 10 minutes on each interview (data item). In this way, all the researchers in the group got an overview over the entire data material – both the interviews – or field notes – we had contucted ourself, and thouse of the others. Whent I did a workshop together with a PhD candidate, she presented her data and I took notes, getting a broad picture of all her data.

Step 2: Mapping themes

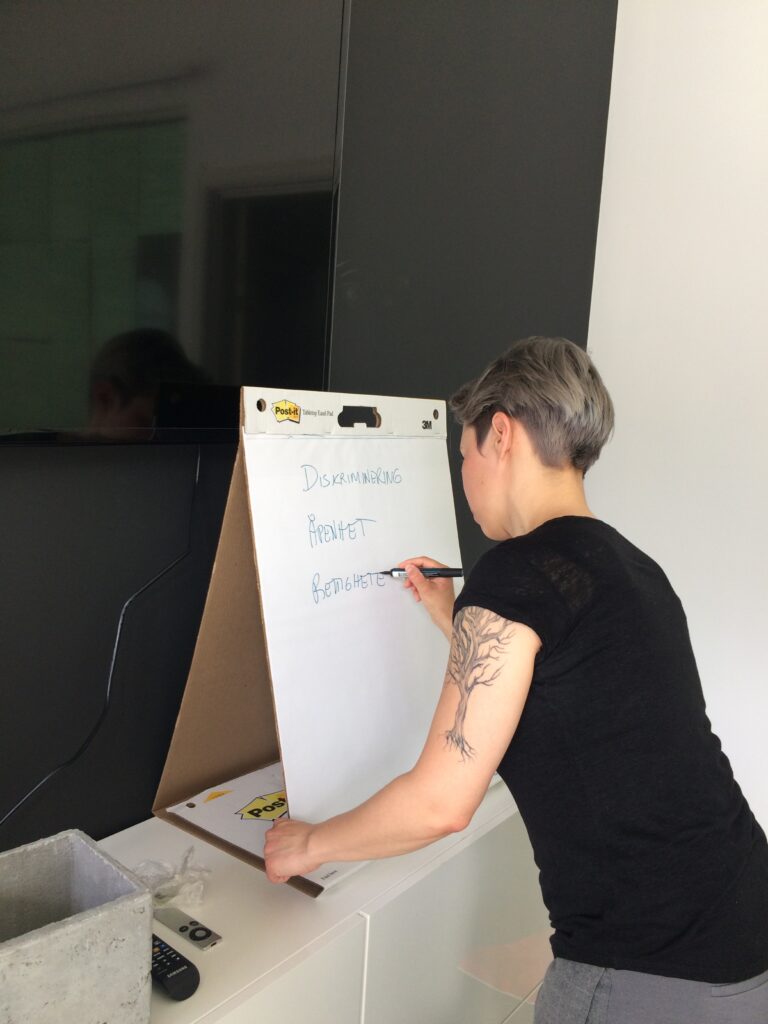

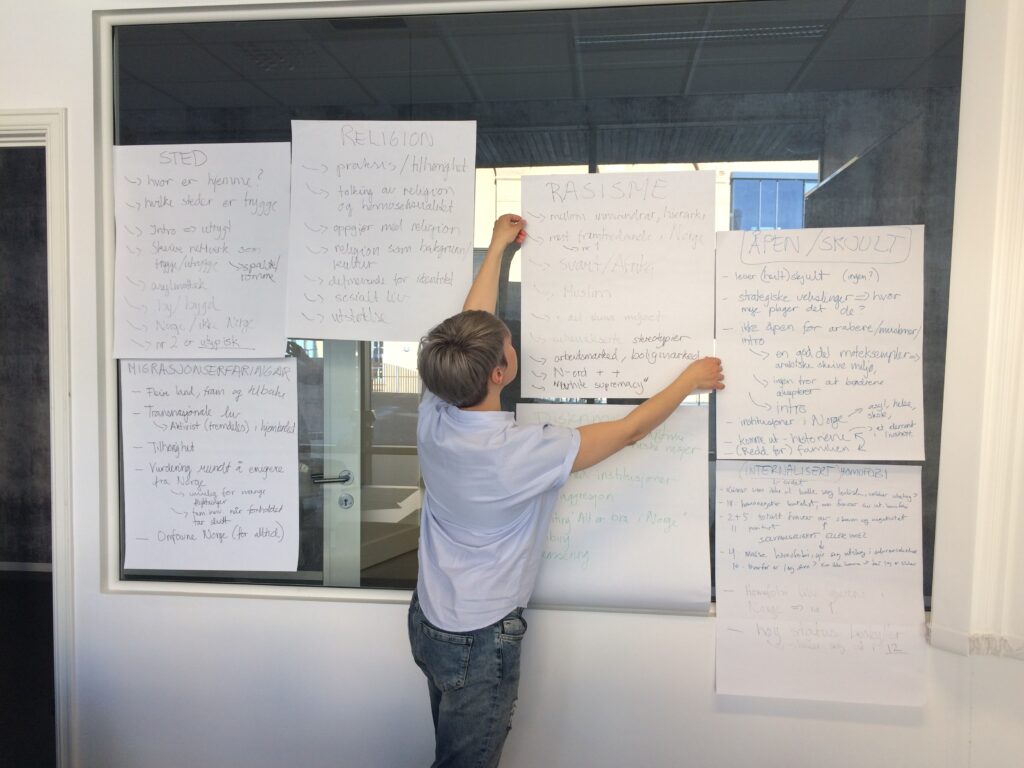

The second step of the process is about mapping themes in the data material. After finishing the first step, all participants had many ideas and thoughts about what we had seen in the data, and now it was time to get it all down on the paper. One of the participants grabbed a pen and wrote a theme on the flip-over. Then, the entire group helped writing notes related to this theme. In the research project “Queer migrants” for example, sexual abuse appared to be an issue in quite a few interviews. Elisabeth wrote “sexual abuse” on the flip-over and we made the following notes:

- A quite frequent theme across interview

- Some were abused as a child

- The abusers are men

- The participants talking about experiences of abuse come from many different countries

- A common narrative is that one has become queer because of the abuse

- They talk about meetings with help services and the police. Many bad experiences, some good.

- Key interviews: 1, 4, 18, 8, 12, 17, 20. In particular number 4.

By the end of this second step of the process, we had identified the following themes:

- Racism

- Living openly or not as queer

- Discrimination

- Homophobia

- Migration experiences

- Place

- Religion

- Sexual abuse

- Laws and regulations

- Norwegian institutions

- Dissapointed over Norway

- Family

- Isolation and loneliness

- Love and coupledom

- Queer networks

- Healh

- Methodological reflections.

During the second step, as we identified themes, we did not open up for discussion. Rather, we added to what other group members said and everyone contributed to the process of identifying themes. Themes are defined broadly and could be theoretical concepts, experiences mentioned in one interview only or appearing frequently across interviews. It could be an abstract theme or a very specific description of experiences or a narrative presented by participants. Our understanding and mapping of themes is inspired by Braun and Clarkes work on thematic analysis. I agree in their view of thematic analysis as a foundational methods that can be applied across different methodological perspectives. Whether you are inspired by discourse analysis, narrative analysis, hermeneutics, conversational analysis or meanings, you can employ thematic analysis.

Step 3: Sorting themes

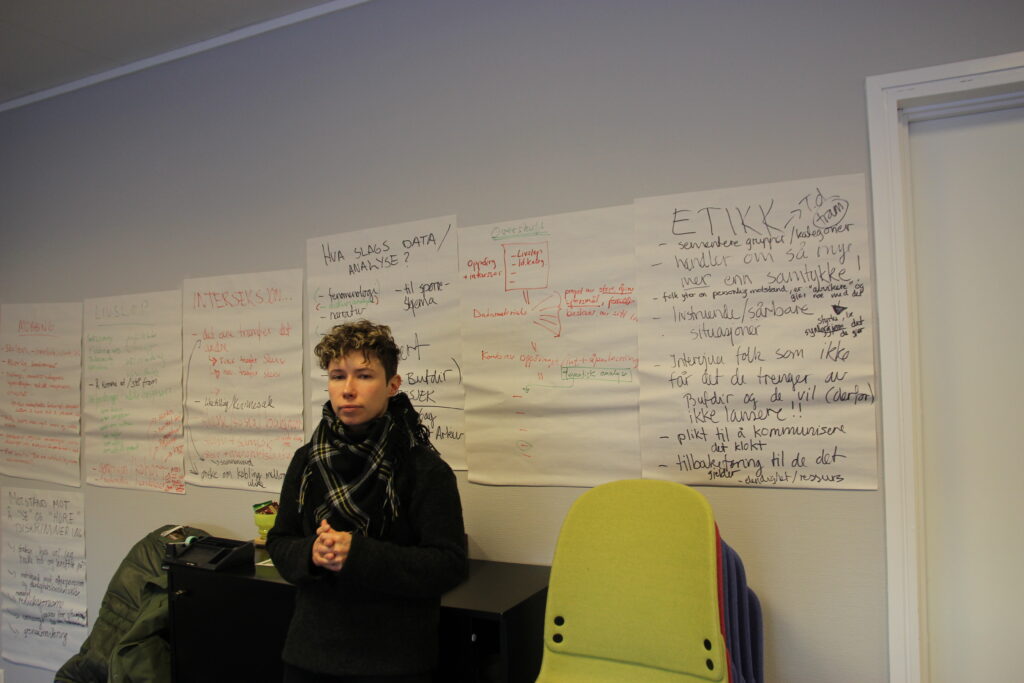

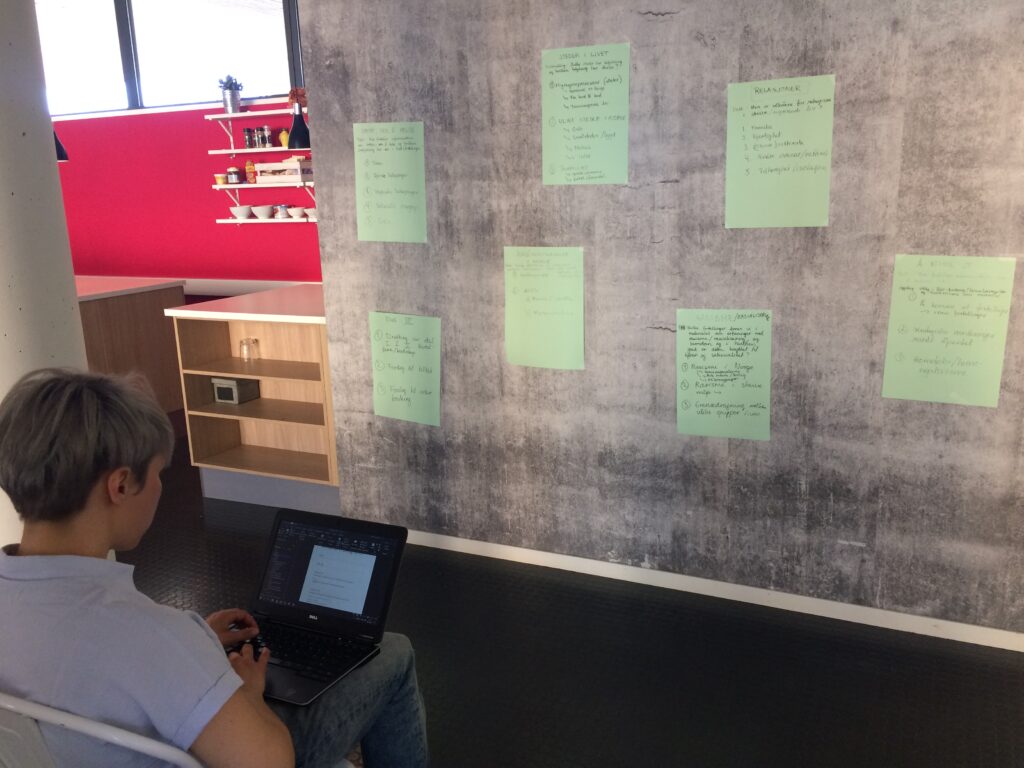

In the third step of the process, we have worked with sorting and group themes by reorganising the thematic sheets on the wall. The physical work of moving have facilitated a process of collective thinking about how themes are related to each other.

In this part of the process, we have asked each other questions, presented different interpretations and oppinions, and identified disagreement. But mostly, we have moved the analytical process forward by thinking collectively.

Step 4: Outline and work plan

The final step of the workshop was to make an outline for the report, the dissertation or the articles we were going to write. We used the themes as a basis for this work and tried to come up with titles, research questions and subthemes for the key themes we had identified during the process of sorting and reorganisation in step 3. Then, we decided who were to start writing on what chapter/article, and made a plan for the writing process.

Why collective research methods?

My colleagues and I have found collective qualitative analysis to be an efficient, creative and enjoyable way of starting the analytical process. Moreover, it has been a good way of handling feelings of despair when faced with large amounts of qualitative data. y engaging into collective qualitative analysis, we can make room for a creative analytical process where we can develop our understandings of empirical data and the process of analysis by learning from each other. I think it would be fruitful to further develop collaborative forms of qualitative analysis and aim to contribute to this endeavour.

Development of qualitative research methods is fun, but also necessary: Current research policies create incentives for large collaborative research projects across disciplines, institutions and countries. Even though qualitative researchers are increasingly expected to be involved in research collaboration, qualitative analysis is mostly presented as an individual endeavour.

Most of all, I hope our work with collective qualitative analysis can inspire you to develop good ways approach the mystery of qualitative analysis. To use Silverman’s metaphor: Perhaps collective qualitative analysis can provide a useful map to explore the unknown territory of qualitative data.

Thank you!

I would like to thank TElisabeth Stubberud, Mai Camilla Munkejord, Walter Schönfelder, Maria Almli, Marte Taylor Bye, Gunhild Thunem, Norman Anderssen, Fredrik Langeland and Cordula Karich for doing collective qualitative analysis with me at various workshops. I sure hope there will be more to come!

Scholarly article: Collective qualitative analysis was first published in Norsk sosiologisk tidsskrift. The original version and an english translation is available at Nordlandsforskning Open Research Archive.